My first trip to Australia, I went with a friend. We were looking for excitement in our trip wanting to contact primitive peoples but we knew that in Australia we would hardly find them. It was when we decided to travel to Papua New Guinea, the island to the north of Australia to know the villages of the Sepik River.

The Sepik is the most important of the six rivers that irrigate Papua New Guinea, a small independent nation since 1975 that occupies the eastern part of the island of New Guinea, in the Pacific. But more important than its notorious physical dimensions, is the fact of being the cradle and shelter of an authentic civilization settled on its shores.

The Sepik is born in the central mountains of New Guinea almost bordering the borders of Irian Jaya, territory of Indonesia that covers the western half of the island. The river meanders the northern part of the country until it empties into the Bismarck Sea, in the Pacific. Geographically and culturally it is divided into three zones: Low, Medium and High.

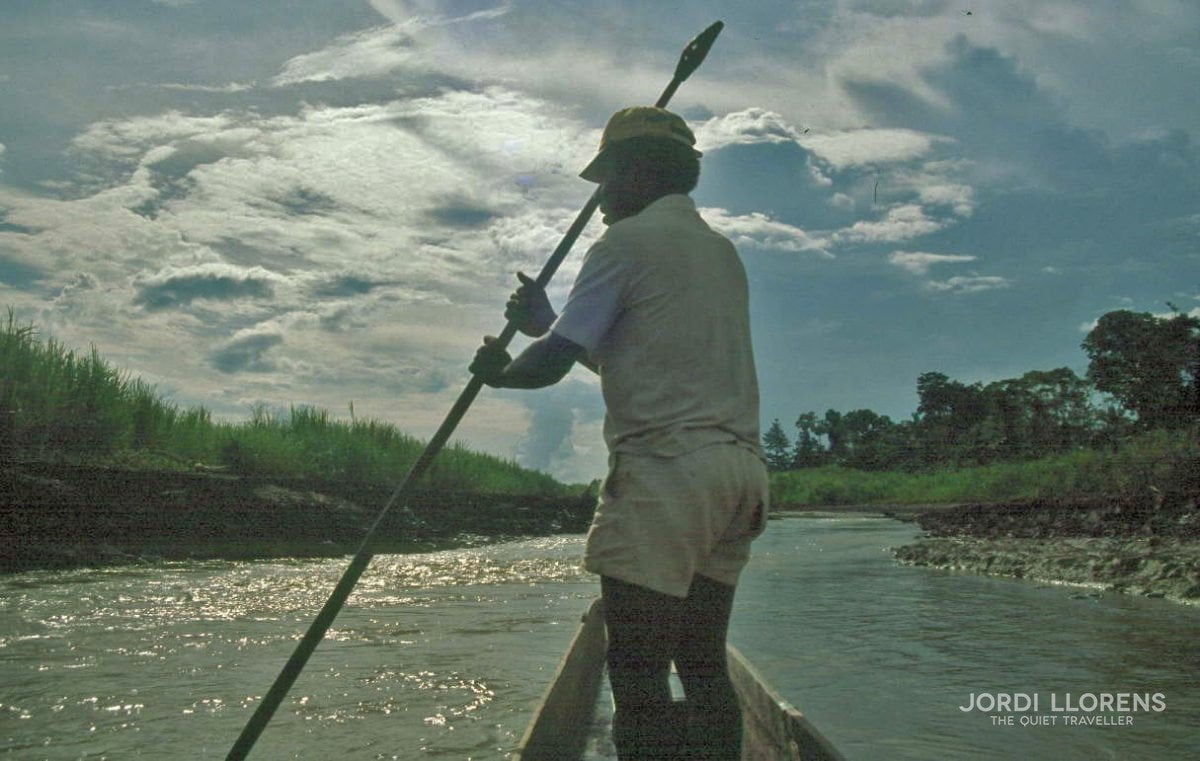

Ready to navigate the Sepik river

But the access to the Sepik was not an easy task. The starting point would be the coastal city of Wewak, arriving by plane from Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea. But this is just the beginning of an adventure that lasts for six hours of dusty travel by bus on a forest track passing by small villages increasingly primitive as we were entering in the interior to meet the Sepik River. The highway dies in Pagwi. From then on, the canoes built from tree trunks emptied from the inside will be the only transport in the Sepik region.

We had contacted a guide called Kowspi, a great expert of the region. We formed a small team: two Americans, my friend, Kowspi and me.

The Kowspi always went ahead the canoe

We sat on some beach chairs placed in the center of the canoe and started to navigate the Sepik. Absolutely unstable, like my fear of falling into the water.

The dark sky was falling over our heads until spitting water torrentially. It’s very typical of the tropics. No raincoat or umbrella. Floods catch you unprepared at the least opportune moment. Water and more water was filling the boat … but the bad times are compensated with the good ones. Kowspi was an artist at this point. He knew how to keep calm in the most delicate moments. He knew how to make you feel cozy in moments of rest.

Upstream we find the most remote and primitive village of the route: Sio. They welcomed us as true gods. They looked at us curiously from a prudent distance in case our anger went beyond what was allowed. A bad attempt to pronounce a word in their language was the funiest reason to be closer to them. Obviously we were not the first to tread on that land. The scummy rests of the T-shirts worn by the children were a real proof. Once again the word of God had tried to Christianize simple people who knew only of the exact natural process of things. But apparently the missionary had begun to give up trying to let everything flow as before, perhaps because when you force things, they tend to break or disappear, if not, to turn against you.

The haus tambaran, the house of the spirits where the population gathers

The morning act of washing our faces or teeth was a novelty that mothers and children did not want to miss. They were not sure what the white foam that came out of our mouth each morning meant. The invisible ties between cultures were woven as the days passed. We sang, they sang to us, we repeated incessantly unpronounceable words and we became acrobats of the unwritten expression.

In the villages we were greeted with surprise and curiosity

To eat, the Kowspi prepared every day a fantastic boiled rice. There was no more left. If I had not liked the boiled rice, there I found it “nouvelle cuisine”. The day that animated the food with a plate of tuna, sardines or vegetables was a party. In fact the food was the least of it. I fed with the company, with what I was living.

Before going to bed we would gather around the fire every night and tell us stories of his ancestors, as when the old people of the villages proceed to orally transmit the tradition to the little future men. There are few things in the world that make you shudder until the last cell of your body. One of them is to receive the message of love for a country from the hands of an unconditional lover of their customs. Kowspi was like that. He loved his land and you ended up feeling part of the leaves of the trees and the trunks of the cabins.

We slept with a mosquito net. The mosquitoes were military helicopters (because of the noise and so big). Malaria in that area was rooted like the roots of its huge trees.

One of the experiences that impress me the most was when we arrived at a town whose name I do not want to remember, silent and empty. All its inhabitants had gone hunting. Only a halo of life. So small that she took the air in sips for not waking up the death. Her God kept her clinically alive pending a thin umbilical cord that sustained her slow and blinded breathing. She was an old woman waiting for death in a fetal position, naked. Her eyes hardened by the sun looked at us but they did not see, however they disturbed us as if they spoke to us of other times and interrogated us about our presence. There I received my first beat of grace. The people of Papua establish that the value of life stops quoting as soon as you get old. Only death can be expected. It was an impact recorded in my memory, in my soul and in my being. With a nervous pulse I pressed the button of my camera in order to reflect once again situations that you do not get used to and that in no way leave you insensitive to old age and death. And I realized what I still had to learn. To learn from life, and to accept its end when nature renews you the return ticket. How little our society teaches us to recognize, understand and accept the darkness of our days!

Waiting for the death

After ten long days without a clock, slowing down our pulse to those people, we had become accustomed to our own stench. Beard of Robinsons and clothes to waste. And we let out a stale whiff of fish. The invisible ties were not only built between cultures, but also among us a connecting thread was born that made us accomplices of a situation that put us to the test as human beings.