I left well prepared from the capital of Namibia, Windhoek, with a 4×4 and a trailer, where I had everything I needed: from food to the tent. I was accompanied by a guide, Bastian, who was one of the few who the himbas had made him their favorite son, and his assistant, Joseph.

Within the territory of the Kaokoland I arrive at Orupembe and, at that moment, you don’t see anything, but, when I get out of the car … I couldn’t believe it! Suddenly I see a group of himba children playing among them! My joy is immense! I approach very slowly not to scare them away, but they are stunned when they see me. I try to smile, I make a gesture of approach and finally I decide to kneel in peace of sign. Once the surprise is over, the smiles explode again. The children shout, they surround me, they hold my hand … Everyone wants to touch me!

I know that I am now at the gates of another world, the world of clans and tribes. I am faced with a great discovery: the himba people, one of the most peculiar ethnic groups in Namibia. At last I began to live my dream!

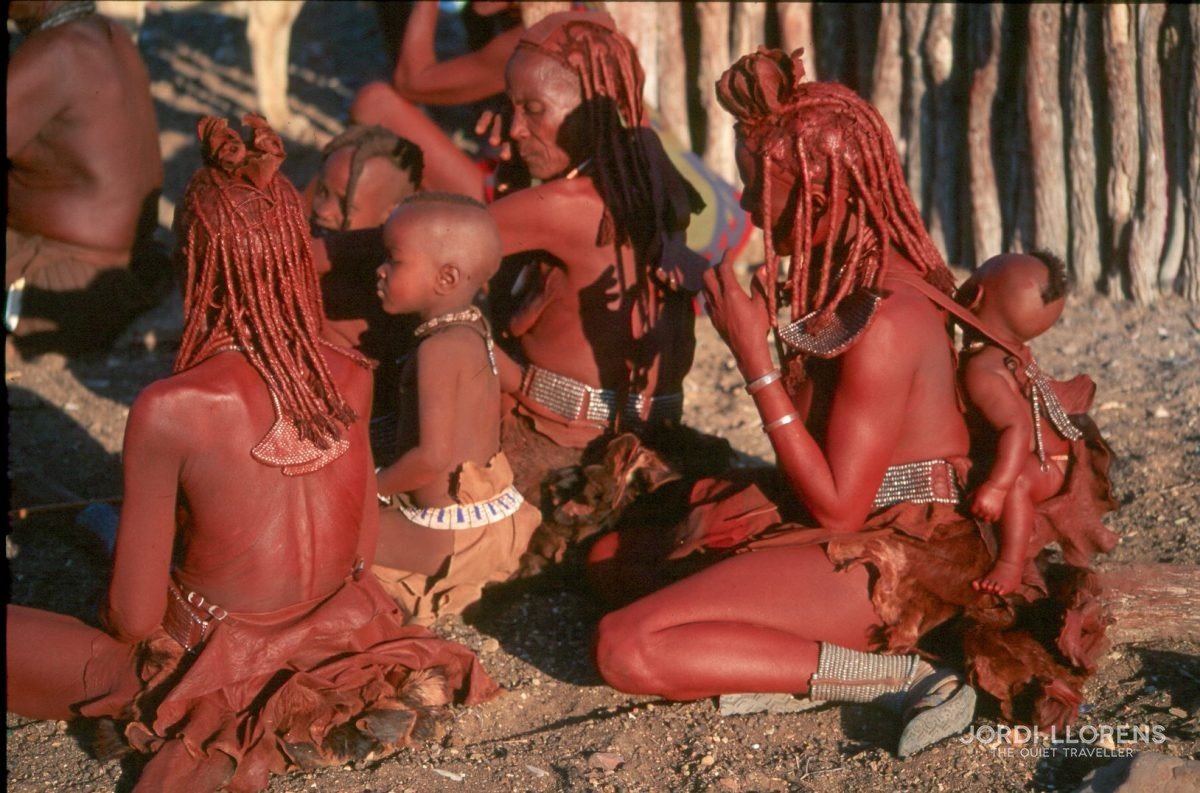

The himba women anoint their bodies and hair with the otjize.

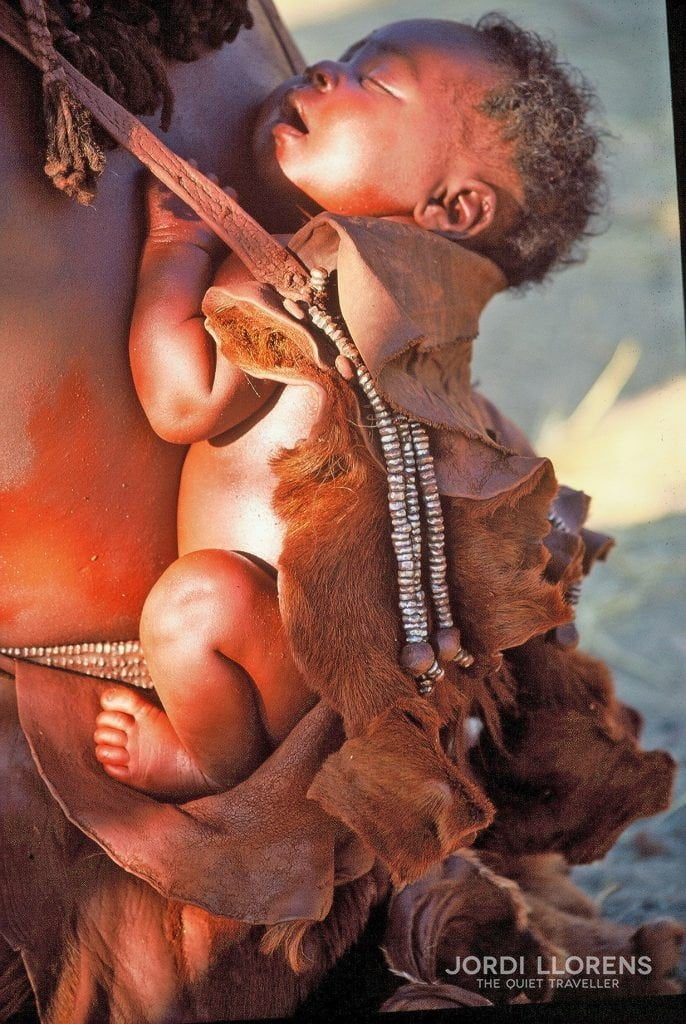

I decide to continue with the children and follow them until they reach their village, which, like all of them, is surrounded by thorny branches that serve to protect them from wild animals. The settlements, called ongandas, are made up of a corral, the kraal, which is located in the middle and which serves to close and protect the cattle, and the huts, which are located around it. But every village has a special place, the okuruwo. It is where the rituals are made, and you can never cross in the middle. These rituals include childbirth, the imposition of names on newborns, puberty, circumcision, marriage and death.

The himba build their huts, with mud, branches and cow dung. Building and repairing them is a women’s work. In each one lives a family. If the man is polygamous, each woman has her own house for herself and her children.

When the children are teenagers, they move on to another hut, and the elderly maintain their independence and live alone.

I give them milk and tobacco. Since we can not communicate, I sit next to them to observe. They do the same with me. It is a mutual feeling. In the middle of the afternoon the families of the village begin to arrive with their goats and lambs. They invite me to spend the night with them, which I accept without hesitation.

The next day, when the sun is just pointing on the horizon, the women are already moving bustily from one side to the other. Some run to the cattlepen to milk. As an essential food, the milk must be presented each morning to the village head to give the authorization to feed the cattle. Then men and cattle begin their daily routine.

One of these daily routines is to take care of their image. Both men and women are easily recognized for their looks and beauty. They care a lot for their dresses and ornaments, although more than for their ornaments, they are better known for the bright red of their skin. For reasons of aesthetics, and also to protect themselves from the sun, they rub their bodies and hair with a reddish colored substance called otjize. It is obtained from a stone, the red hematite. They crush it into a kind of fine powder, and then knead it, mixing with cow’s butter. From this mixture you get a thick reddish cream that is carefully spread all over their body, and even the clothes, dyeing everything red. Women also put on bracelets and necklaces. This penetrating smell of cow excites both men and women and makes them more attracted to each other. The otjize seals the alliance of land and cattle over the body of women. After a few days I was totally imbued with that smell so characteristic of the himba women.

The clothing of the himba is made of goatskin

They dress a folded loincloth, made of goatskin. They are adorned with all kinds of jewelry, bracelets and leather ornaments that adhere to the neck, waist and ankles. They never remove them during the day even for work. The most important piece of adornment is a large white shell that is worn as a necklace between the breasts. This valuable shell is a symbol of fertility, as well as an omen to wish happiness to a girl in her entrance to life as a woman, and is inherited from mothers to daughters.

I admire their hairstyles, which not only have an aesthetic function but also serve to express sex in children and social status in adults.

While the men take care of the cattle, the women carry out the housework and take care of the children. Also the task of grinding wheat is done daily using the primitive mortar and stone mass as it was done in the Neolithic, because the himba, until fifty years ago used tools of stone and wood.

The main diet is meat, milk and wheat.

Cattle is not only decisive in the economy but is the center of the life of the himba. A himba without cattle does not count as himba. They extract the milk, the cottage cheese on which their diet is based, the manure which they raise their houses and the skin that dress them.

Their main diet is meat, milk and wheat. Formerly, when they were nomads, the villages barely lasted a few months in the same place, but increasingly they have become more sedentary thanks to the location of wells, which give them constant water and the water mills that they have been building, since they roam with the flocks in search of pastures to feed the animals.

The health of the himba is quite good if we consider that due to their isolation they have been preserved from epidemics and infections from the outside world. They are athletic, strong and do a lot of physical exercise, since they usually do long walks with the cattle.

When they get sick there are healers or otchimbanda who, apart from guessing, have therapeutic skills and enjoy a good reputation.

The himba are monotheistic, although their religion does not revolve around God. For them the supreme being is Ndjambi, because for them the word God is too sacred. Their religious dimensions are not visible in the worship of God, but in the homage to their ancestors.

On the way, and away from the villages, I find cemeteries. They do not have a fixed place. When a himba dies, they take to bury on shoulders, if they can not walk more it means that the dead man wants to be buried there. That is when on the stone slabs are placed the name of the deceased and the horns of their favorite buffalo. The meat of the cattle is not eaten for respect to the deceased because they were animals that the person who died loved so much. It is about sending the spirit of these animals in eternity, together with their owner they bury wrapped in the skin of their favorite bull. After 6 to 12 months they return to the cemetery and sacrifice two bulls. For three days they celebrate a party in which they eat in abundance. This party is done to remove the duel and help the dead to cheer its spirit.

I hope that the himba can continue to maintain the sacred fire and the memory of their ancestors. His way of living can teach many things in our society. Although we are more proud of the technological development we have achieved, more and more we have more difficulty adapting to the accelerated pace that this imposes us. Traditional societies have managed to preserve their biorhythms more harmoniously with nature.

Throughout a lifetime, himba women have learned to show their feelings and experiences through external signs: hairstyles, jewelry and ornaments that mark changes in their social status. Their eyes talk about their feelings in a world made up of many rules and few words.